Table of Contents

The Naming of Fossils: Taxonomy

“Taxonomy” is the science of naming and classifying living and fossil organisms. Often regarded as one of the most boring aspects of paleontology, taxonomy could never be considered as anything other than a “necessary evil” except to the purists. However, it is one of those “boring but important” subjects that requires some discussion. It is probably the intricacies of paleontological taxonomy (“all those Latin names!”) that has done most harm in making paleontological information less accessible to non-specialists than any other aspect of paleontological study. However, it is a subject that geoscientists who frequently have a need to use paleontological data should be familiar with, as it often impacts of whether a particular fossil species or group is considered “valuable” for interpretative purposes.

Early paleontological taxonomic hierarchies grouped organisms based on physical similarities – simply put, if two organisms (or fossils) looks like the same shape then they are probably related. For example, during the early heyday of international whaling, many seamen regarded whales, dolphins and porpoises as fish rather than as mammals. Modern schemes, more correctly, follow evolutionary relationships and only relate two separate organisms if it is thought they share a common ancestor.

The basic unit of naming any organism – fossil or living – is the species, for example our own species – Homo sapiens. Higher units (in order of ascendance) include the Genus, Family, Superfamily, Order, Class & Kingdom. The originator of this method of naming organisms was the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778). Since then, the “Linnaean classification system” has been variously modified to include categories such as subspecies, subgenus, subfamily, suborder and subclass but essentially the hierarchical nature of the system remains the same.

The right to name a new species belongs to the person who discovered or first observed it and who has published those findings in an accepted journal or book. It can be accepted or rejected by fellow scientists who may agree or disagree with the initial “diagnosis” – this is the nature of scientific freedom and advancement. But already we can see the seeds for future confusion being sown! We can illustrate how an individual fossil species is assigned a name and how that name might change because of further study and knowledge…

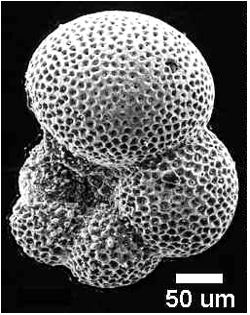

A formally described species must have two parts to its name: Genus and species. Convention recommends the initial letter of the Genus name is capitalised, the species name not capitalised and both names are italicised. For our example species (a planktonic foram from the Paleocene)…

Parasubbotina pseudobulloides (Plummer, 1926)

This species was discovered by Helen Pummer who reported it (illustrated, diagnosed and described) in a published journal in 1926. However, Dr Plummer did not originally assign her new species to the genus Parasubbotina – that name did not exist in 1926. She originally called her new species Globigerina pseudobulloides. We will see why the genus name has changed later but we can instantly see this has happened in our example because Helen Plummer’s surname and publication date has brackets around it. If there had been no change in the genus name then there would not be brackets around the author’s name. This is the conventional way of showing such change in the scientific literature.

[Note: in the conventional literature, once the species has been fully named in an article’s text (genus and species) the genus name is often abbreviated in subsequent instances in the same article. In our example this would therefore be P. pseudobulloides. Such abbreviations may also be used on charts and diagrams.]

In the normal course of events in biostratigraphy, the species name (i.e. pseudobulloides) will generally be quite stable… unless the same organism is separately described under two different names by two different authors without the other’s knowledge. The one described and published first takes precedence, the second (or later) name then becomes what is known as a synonym. This can happen when scientists working in two different countries on the same material may not be aware of the other’s work and who publish in separate journals. The vast majority of fossil species were described in the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries when international scientific co-operation and information interchange were much less prevalent than they are now and this situation arose many times. Scientists who have come along later, so to speak, have had to deal with these historical anomalies every since. See also comments on “Splitters and Lumpers” below.

Unlike the species name, the Genus name, however, may change relatively frequently, based on changes in how groups of organisms are classified either based on functional similarities or on evolutionary relationships as discussed above. In our example above, the same taxon (the species “concept”) has been referred to variously, and for quite valid reasons at the time, as:

Globigerina pseudobulloides

Globorotalia pseudobulloides

Subbotina pseudobulloides

Morozovella pseudobulloides

Turborotalia pseudobulloides

[…or abbreviated to G. pseudobulloides, another G. pseudobulloides (which one? – another source of confusion!), S. pseudobulloides, M. pseudobulloides and T. pseudobulloides!). Not to mention one other author who considered this taxon to be a variant of a completely different pre-existing species which was therefore named Globigerina compressa var. pseudobulloides!]

Different genus names have been assigned over the years to reflect the progress of our understanding as to the evolutionary relationship of the species we know as pseudobulloides to its closest or more distant relatives and its overall position in the evolutionary history of the planktonic foraminifera as a whole. Such earlier names are also placed “in synonymy” with Parasubbotina pseudobulloides. For the time being it resides in the genus called Parasubbotina – a name which did not exist until 1992. No-one knows if or for how long this name will remain valid, as and when we discover more and more about this particular species.

Subjective Synonymy

A different type of synonymy also exists where a paleontologist has miss-identified a specimen in their material, but published it anyway. Later, another paleontologist comes along and re-examines the first paleontologist's illustrations (or preferably the original material) and decides that the identification was mistaken but suggests what it should be called. In the second paleontologist's publication, he/she will refer to the first paleontologist's record as a “subjective synonym” (subjective because it is the second paleontologist's opinion).