Table of Contents

Foraminifera ("Forams")

Forams are single-celled animals (“protista”), heterotrophic (which means they require food from an external source, just like we do) and some are a heterotrophic/symbiotic combination. Think of an Amoeba from your high-school biology class, but with a shell. Most have a mineralised wall of some kind (there are some rare “naked” forms): a secreted wall will be calcareous (calcium carbonate - CaCO3) of various crystal arrangements; an agglutinated wall can be comprised of any externally-acquired material (usually sand/silt/mud particles) with a calcareous, non-calcareous or organic cement. Only certain benthic (bottom-dwelling) forms exhibit agglutinated shells.

Forams are single or (mainly) multi-chambered. All chambers possess one or more openings (Latin; “foramen” - which gives them their name) which connect to other chambers. The arrangement of chambers can show a great many forms from fully coiled multichambered forms to tubular single chambered types. The combination of that and other features has resulted in the identifications of tens of thousands of living and fossil species. They inhabit virtually every marine & marginal marine aquatic niche on earth. They are biostratigraphically and palaeoenvironmentally significant and the predominant subject of study for microfossil specialists.

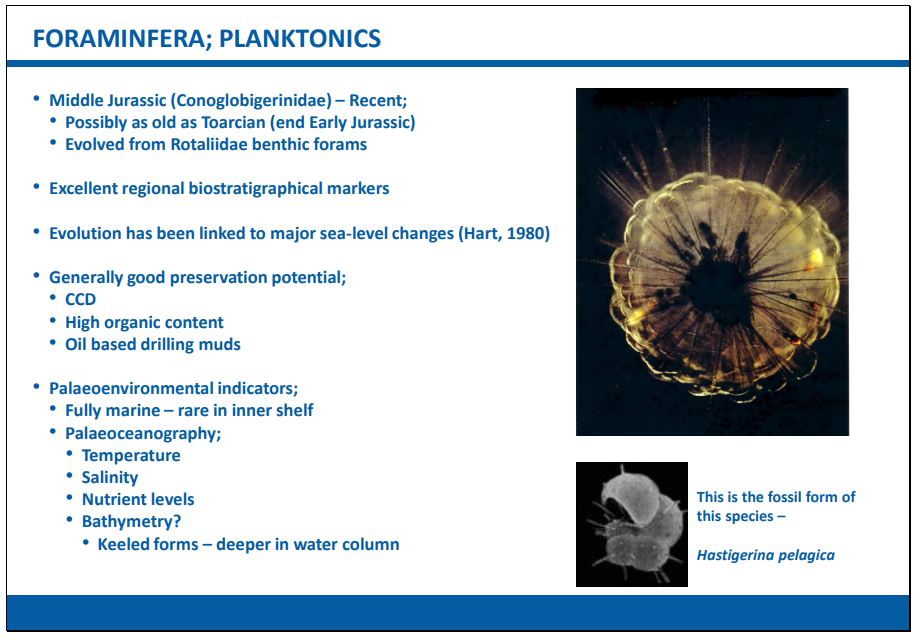

Subgroup: Planktonic Forams

They have a calcareous (secreted hyaline) shell structure. Their geologic range is Middle Jurassic – Recent (they are still living – “extant”). They inhabit open marine water depths between the surface and several thousand metres (over the course of the normal life-cycle) but live mostly in the top 0 – 50/100m of the water column. Many species exist with symbiotic algae and therefore mainly inhabit the photic zone in eutrophic waters (waters with little or no nutrients) to allow the algae to photosynthesise and provide nutrition. When they die the shells sink down through the water column to become part of the marine pelagic sedimentation. The shells can accumulate in such high numbers that deep sea sediments comprising mainly planktonic foram shells are called “Globigerina Oozes” (after a common genus name in planktonic foram naming).

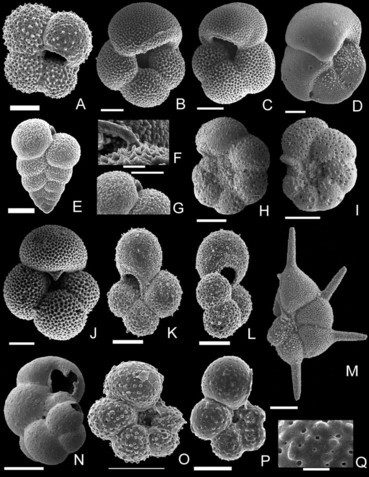

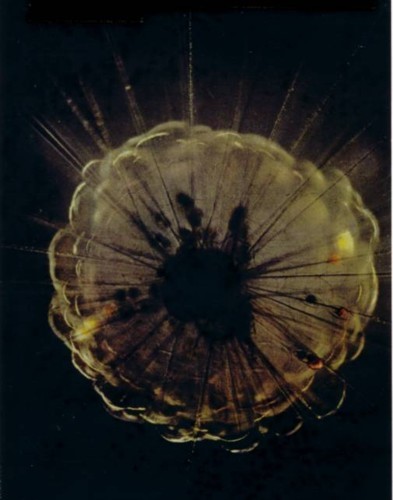

Left: Various fossil planktonic forams from the Cenozoic. The aperture (terminal opening) can be seen on several specimens and forms an important part of determining the genus and species of a particular specimen. Right: A living planktonic foram – note the bubbly protoplasmic material which aids buoyancy, supported by spines which are lost on fossilisation. The shell is the dark mass in the centre.

The percentage of planktonic forams in individual fossil foraminiferal assemblages tends to increase (up to 90%+) with increasing water depth therefore statistical measurements of an entire assemblage in a sample can give useful paleo-water depth indications. They are rare at depths shallower than middle shelf (because there is insufficient water depth to carry out the breeding cycle), evolve rapidly, and provide excellent stratigraphic resolution

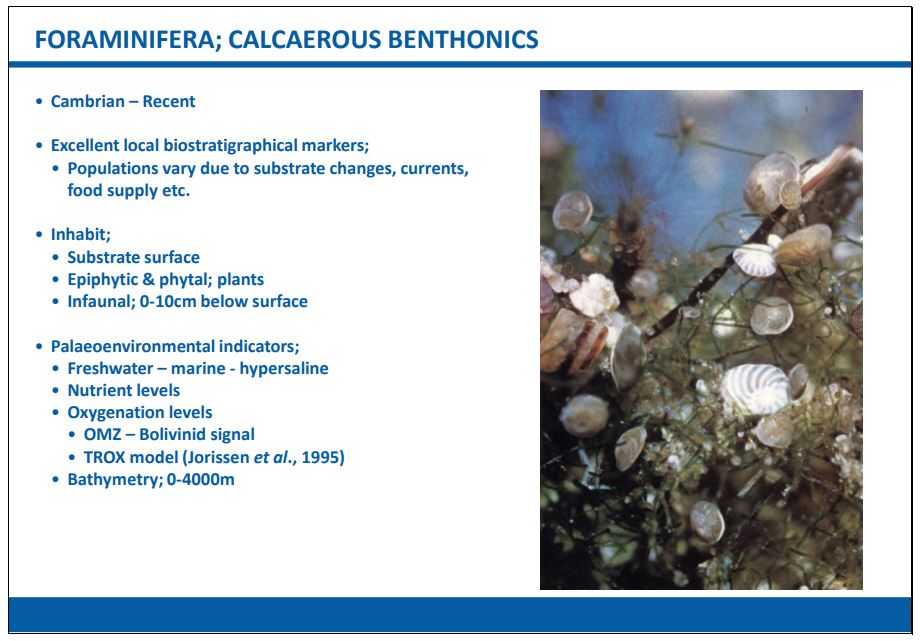

Subgroup: Benthic Forams

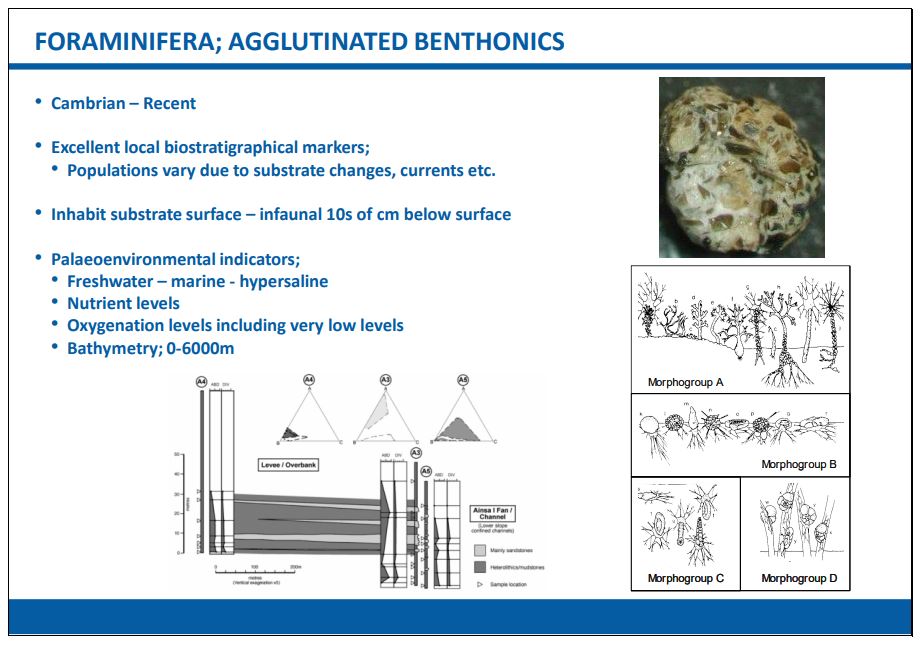

A further subgrouping separates Calcareous (secreted hyaline, aragonitic or porcellanous CaCO3) shelled forams or Agglutinated (the accretion of externally-derived particles to the cell’s surface) forms of wall structure.

Benthic forams (which cannot swim or float and therefore live “on the bottom”) are hugely diverse and there are many, many more species than their planktonic counterparts. Their geologic range is Cambrian – Recent (they are “extant”).

Left: Various fossil benthonic forams from the Cenozoic. These few examples show only some of the ways in which successive chambers can be arranged. There are numerous other examples of chamber arrangements. Right: A living benthonic foram in a sea-grass community. These forms are characteristic of warm, clear, shallow water and often grow up to relatively large sizes (several centimetres).

Benthic forams inhabit virtually all marine sediment substrates either on top of (“epifaunal”) or burrowing within (“infaunal”) including hypo- and hyper-saline environments and can also live on the surfaces of plants (“epiphytic”). Naked, unfossilisable forms may occur in freshwater.

The agglutinated forms without any calcareous components in the shell predominate in ultra-deep waters (below the CCCD), more restricted environments and/or in conditions of low dissolved O2.

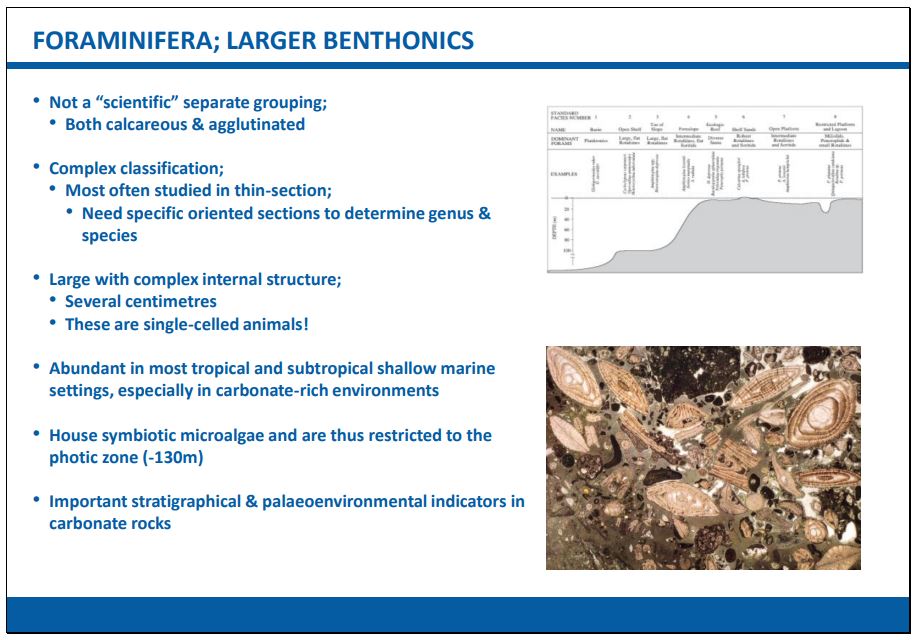

Sub-subgroup: Larger Benthic Forams

Some benthic forams can achieve large sizes (perhaps even up to 10 cms in length - remarkable for a single-celled organism!) under warm, clear waters with the incorporation of symbiotic algae within the shell as an additional nutrition source – these are often grouped under the term “Larger Forams”.

Benthic forams generally can be used to provide very useful paleoenvironmental information and, combined with planktonic forams, can be used to estimate paleo water depths.