Table of Contents

Typical Environments and Their Fossils

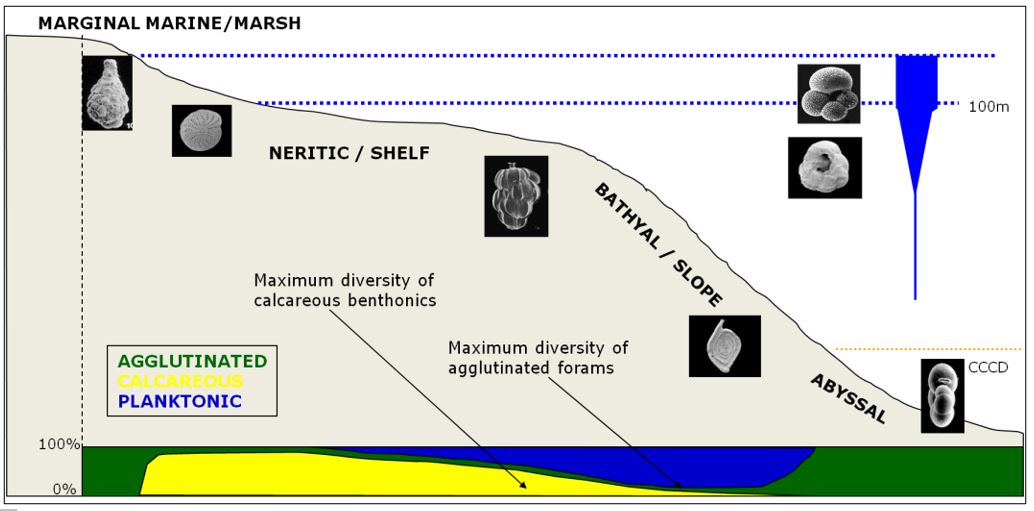

Predominantly based on benthonic organisms as these are more responsive to substrate conditions. However, the planktonic component of a fossil assemblage is useful for estimating paleodepths.

Foraminifera (both benthonic and planktonic varieties) are the best microfossils to evaluate paleoenvironments. Many foraminifera have reasonably well-known environmental and bathymetric distributions.

Distribution of living foraminifera in the hydrosphere. Proportions of the three main foraminiferal groups in fossil assemblages are shown in the bottom strip.

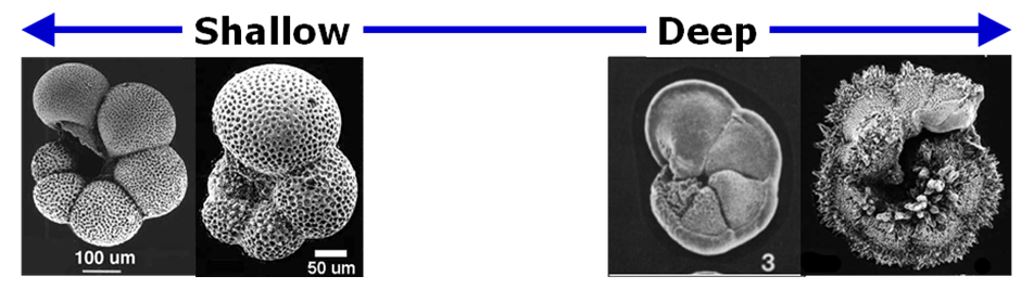

Different shell shapes of planktonic forams (keeled or non-keeled) reflect habitat-differences in relative water depth.

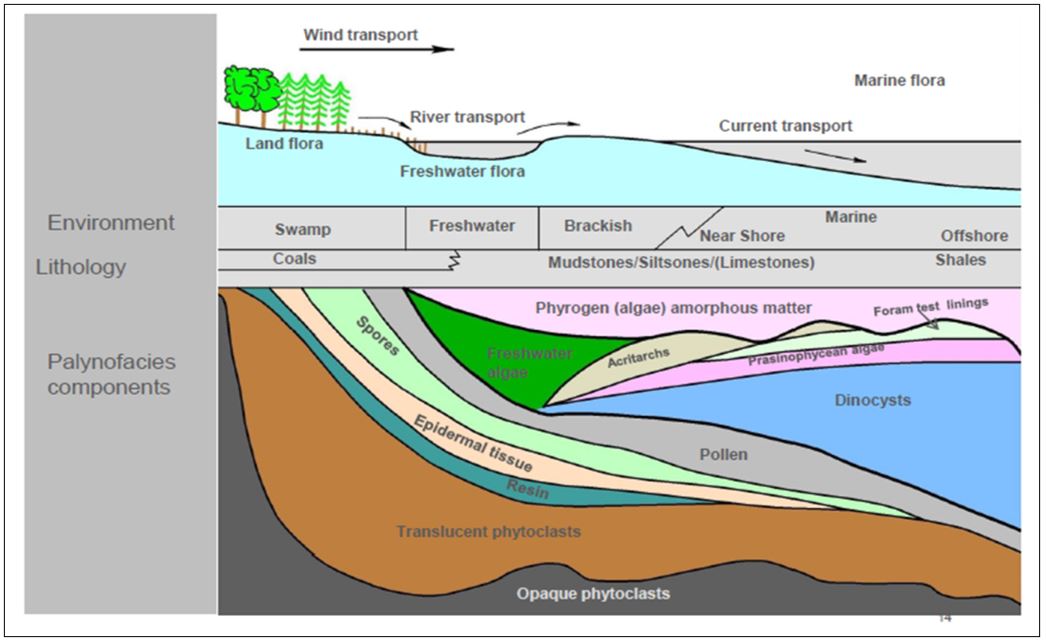

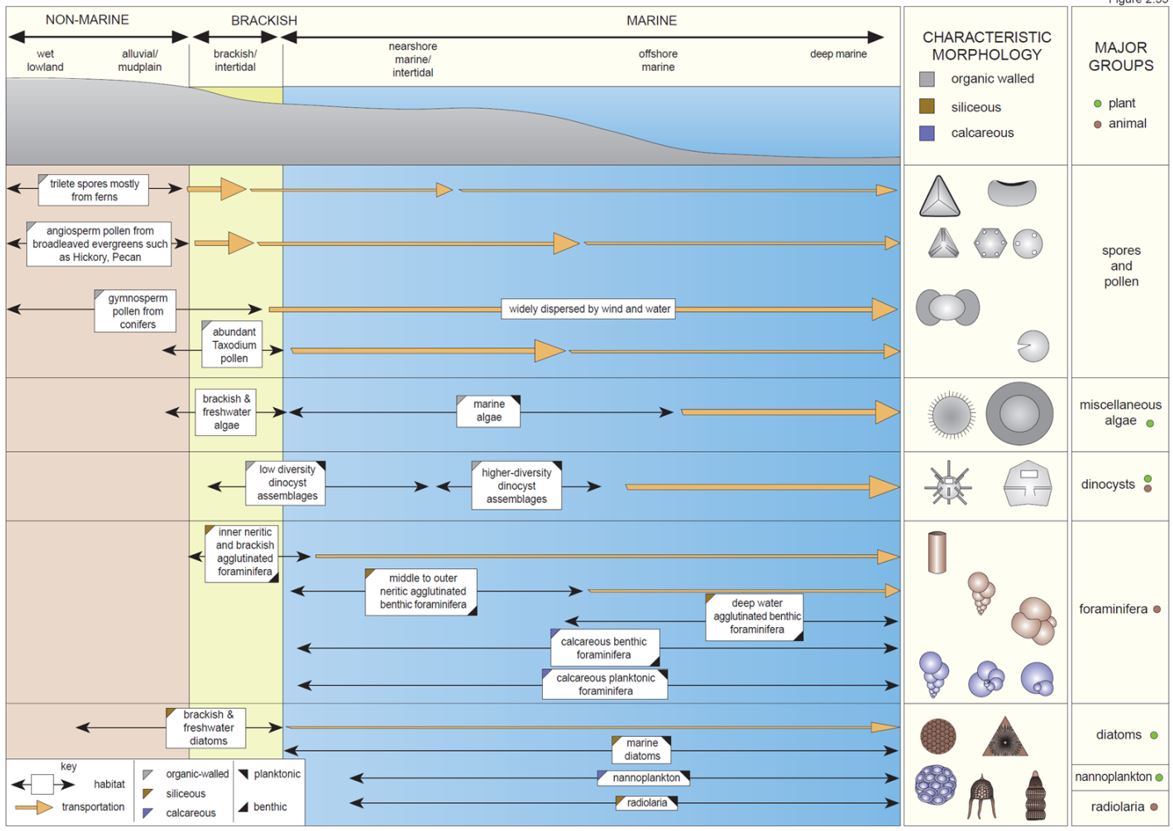

Groups such as ostracods can also be useful. Other planktonic microfossils can give more generalised information. Combination studies of various palynomorphs (often referred to as “palynofacies”) can also give useful paleoenvironmental and paleoclimate information.

Details of palynological components and their proportions in terrestrial and marine settings (courtesy of Katrin Ruckwied, Shell).

Palynofacies - A term often seen in conjunction with typical biostratigraphic reports is “palynofacies”. This is a quantitative technique which examines not only the various species of palynomorph that make up an assemblage, but also the other organic matter (kerogen) contained within a palynological preparation. It also assesses - by means of measuring the colour of certain palynological objects such as spores - the degree of thermal change that the sample has undergone during burial. Palynofacies can provide a detailed paleoenvironmental breakdown of a succession when trends in these signals can be plotted.

The uses of colour in fossils to determine thermal maturity is covered in more detail here [NEED LINK]

A combination of data based on different microfossil (or macrofossil) groups is the most powerful tool for determining paleoenvironments.

Summary chart of the broad distribution patterns of the main microfossil groups (courtesy of Dr Jonathan Bujak, the Azolla Foundation).

In addition, numerous statistical methods can be applied to fossil assemblages.

Shape variation in Operculina ammonoides is related to depth of habitat. Measuring the dimensions of a species assemblage can be applied statistically to paleoenvironmental interpretations.

The Composition of Some Typical Environments

Attempting to comprehensively categorise every discrete environment on earth with a list of their faunal and floral components would be impossible in the context of this manual. However, it is possible to make some general remarks, together with a description of the characteristics of the most common fossil groups likely to be reported in the literature.

- Terrestrial

Fossils very sparse and sporadic in terrestrial sediments; irregular distribution; land plants or animals (vertebrates etc.); probably spores & pollen in palynological preparations.

- Terrestrial Fresh-Water Aquatic (ponds & rivers)

Land animals and plants, some fungal species and spores & pollen in palynomorph preparations; possibly freshwater ostracods and diatoms. Fossilisation potential in riverine sediments is very low for microfossils, even if they could exist there.

- Terrestrial Fresh-Water Lakes

Frequent ostracod species (no easy way of differentiating fresh water from marine species without specialised knowledge); spores & pollen in palynomorph preparations.

- Terrestrial Brackish or Salt-Water Marshes

Low diversity assemblages but possibly high numbers of individuals; agglutinated foraminifera & ostracods common; spores & pollen in palynomorph preparations.

- Marginal Marine

Mangrove belts, estuaries etc. Low to moderate diversity assemblages but possibly high numbers of individuals; some agglutinated foraminifera & ostracods common; spores & pollen in palynomorph preparations as well as high numbers of mangrove pollen.

- Hypersaline Lagoons

Species tolerant of high salinity levels; common “porcellanous” foraminifera of the Order Miliolidae (“miliolids”).

- Shoreface / Intertidal Zone

A difficult environment for many organisms with frequent exposure and submergence to cope with. Bivalves/brachiopods possibly common. Microfossils are rare to absent.

- Marine (Inner Shelf: 0-50m water depth)

A highly productive environment with abundant infaunal (within…) and epifaunal (on-top-of… the sediment) organisms as well as epiphytic (dwelling on plants) organisms (e.g. bivalves, brachiopods, echinoderms etc.) with microfossils dominated by calcareous benthonic forms (foraminifera & ostracods). Planktonic microfossils and agglutinated foraminifera are rare (<5%) to absent though nektonic macrofaunas (fish, cephalopods etc.) are common. Reef development common in warmer waters with associated corals, bivalves etc. and, characteristically, “larger” calcareous and agglutinated benthonic foraminiferal species.

- Marine (Middle Shelf: 50-100m water depth)

Another highly productive environment with abundant and diverse infaunal and epifaunal species, although less epiphytic forms. Planktonic microfossils (planktonic foraminifera, nannoplankton, dinoflagellates & diatoms) begin to appear consistently and macrofauna nekton (fish, cephalopods etc.) continue to be common. Ratio of planktonic : benthonic foraminifera around 5-30% planktonics.

- Marine (Outer Shelf: 100-200m water depth – up to the shelf edge)

Calcareous benthonic foraminifera reach maximum diversity levels. Planktonic microfossils continue to increase in abundance with planktonic :benthonic foraminifera ratios increasing to 30-50% planktonics. Calcareous nannofossils and dinoflagellates reach maximum abundances. Macrofauna nekton (fish, cephalopods etc.) continue to be common.

[NB: Locally, shelf basins may show unusually high proportions of diverse agglutinated foraminifera with few or no calcareous representatives where water circulation/mixing is poor and basin waters become “stratified” resulting in low oxygen levels near or at the sea floor.]

- Marine (Upper Bathyal: 200-1000m water depth)

High benthonic diversity levels, still predominantly calcareous forms though agglutinated foraminifera become a significant minor component of the assemblages. Planktonic : benthonic foraminifera ratios reach a maximum of 50-75% planktonics with a moderate proportion of this being keeled forms. Calcareous nannofossils and dinoflagellates continue to show high abundances but begin to gradually reduce further away from the shelf edge as surface water nutrients begin to decline.

- Marine (Middle Bathyal: 1000-2000m water depth)

Similar to Upper Bathyal with increasing proportions of agglutinated foraminifera and further reduction in abundance of calcareous nannoplankton and dinoflagellates. However the planktonic :benthonic foraminifera ratio is still very high (75%+) with an increasing proportion of keeled forms and those with symbionts in the assemblages compared with shallower slope settings.

- Marine (Lower Bathyal: 2000-4000m water depth)

Similar to Middle Bathyal with further increasing agglutinated foraminifera especially when approaching and below the CCCD (if present), or within the co-called “Oxygen Minimum” zone.

- Abyssal Plain

Very high numbers of planktonic foraminifera (almost all forms with symbionts) which frequently comprise 30% or more of the whole sediment and are known as “Globigerina Ooze”. This sediment covers most of the ocean floor (abyssal plain) above the CCCD. Very few nektonic macrofaunal remains are found as fossil (maybe some fish teeth) and specialised, porcellanous forms within the calcareous benthonic foraminifera are quite common. Below the local CCCD depths agglutinated foraminifera comprise almost 100% of the total foraminiferal assemblages.

- Abyssal – Hadal (down to c.11000 metres)

Below the CCCD the calcareous component of the deep-sea “ooze” is removed. Ultra-deep water oozes are predominantly siliceous with high proportions of silica-based microfossils (diatoms and radiolaria). These siliceous oozes are less common in extent than the calcareous oozes. Benthonic organisms include (mainly) agglutinated foraminifera but highly specialised calcareous forms (foraminifera and ostracods) do exist although their fossilisation potential is low.