Table of Contents

Sample Processing & Sample Selection

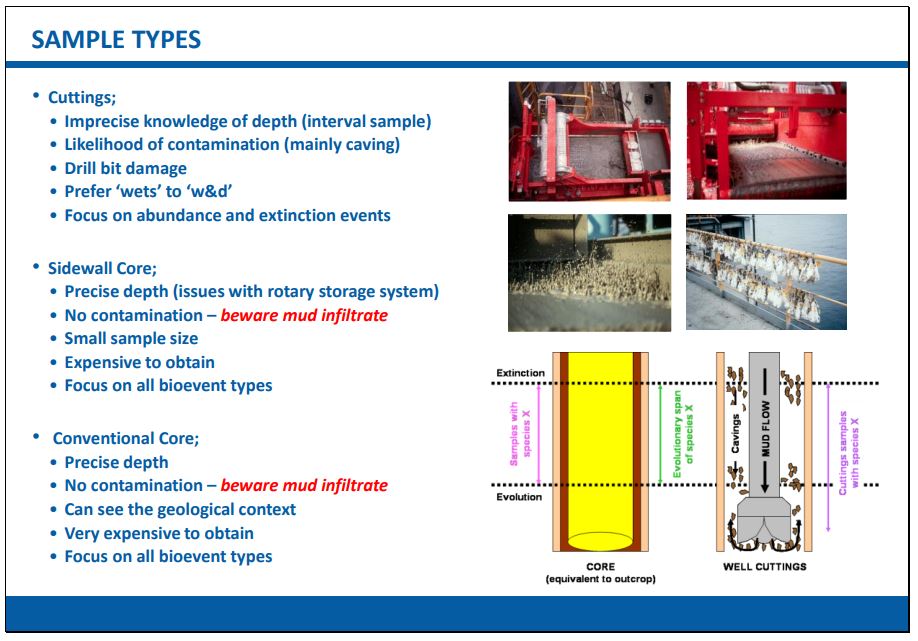

All studies in biostratigraphy, no matter the reason, require rock samples from which to obtain the fossils. Some fossils are found whole in the rocks and can be extracted in one piece (hopefully). Microscopic fossils however - those used most often in applied biostratigraphy - require to be “liberated” from the surrounding sediments in one way or another and concentrated to make it convenient for the analyst to examine as many specimens as possible. It is important that biostratigraphers have a good degree of control over their samples in that they need to know (a) from where exactly the sample was obtained and (b) that the sample is not contaminated with material that has come from anywhere else. This control is often easy to deliver when sampling outcrops at the surface or near surface but much less so when dealing with samples that are obtained by drilling. The drilling process imparts many variables and unknowns into sample generation and collection and anyone who relies on data of any kind from these samples must be aware of such uncertainties.

Samples in commercial biostratigraphy normally originate from the drilling process. However, other sample types are also analysed for biostratigraphy including outcrop samples and sea-bed cores or “grab” samples.

Samples in commercial biostratigraphy normally originate from the drilling process. However, other sample types are also analysed for biostratigraphy including outcrop samples and sea-bed cores or “grab” samples.

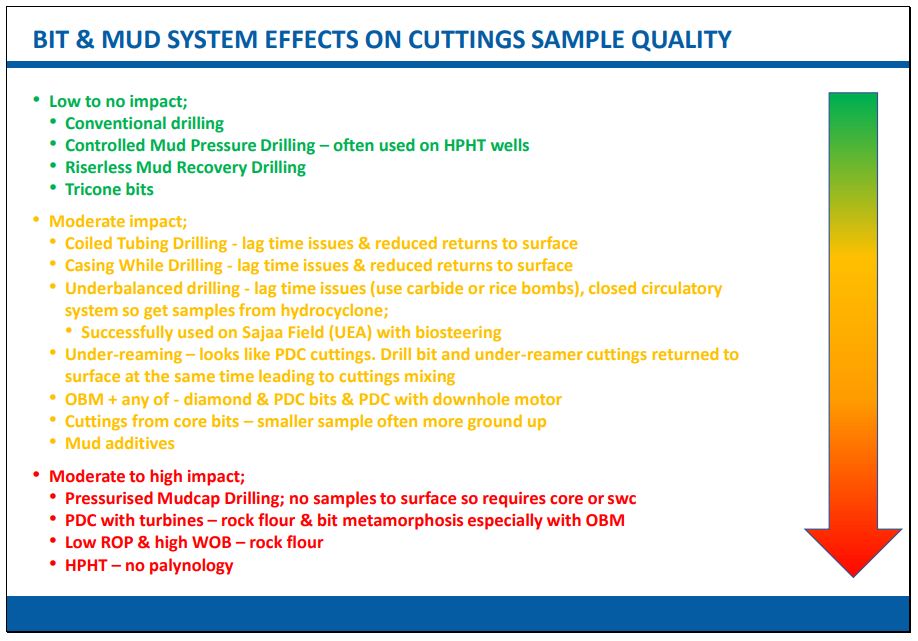

What can effect sample quality from drilled sediments? The choice of drill-bit, mud-type and method of drilling can affect the recovery potential of microfossils from the samples and thus influence data quality.

What can effect sample quality from drilled sediments? The choice of drill-bit, mud-type and method of drilling can affect the recovery potential of microfossils from the samples and thus influence data quality.

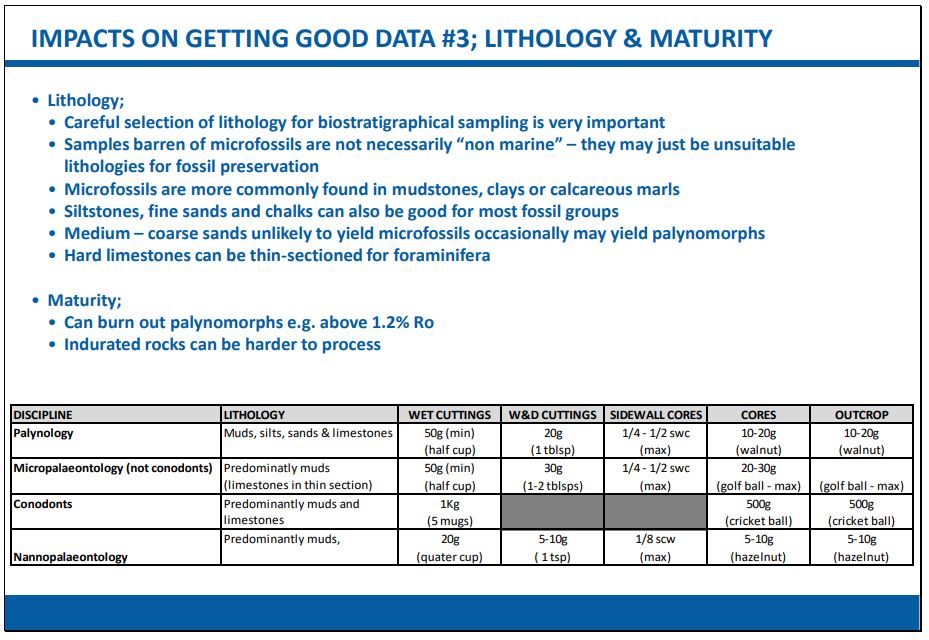

The three main microfossil groupings – in addition to the scientific differences between them – are each also distinguished by the basic processing methods used to liberate the microfossil specimens from the rock matrix, although there are various other detailed differences within the main three methods depending on additional factors. One of the most important factors which determines the likelihood of good microfossil recovery is sample lithology:

- All microfossil types are more commonly found in marine or marginal marine mudstone, clays, chalks or calcareous marls (i.e. the finer-grained sediments)

- Siltstones and fine sands can also be fairly good for some fossil groups

- Medium – coarse sands are unlikely to yield microfossils but may yield palynomorphs because of the “tough-but-flexible” nature of their organic wall structure

- Well-cemented sediments such as hard limestones can be thin-sectioned for foraminifera and other microbiofacies components

- In outcrop and core studies careful selection of lithology for biostratigraphic sampling is therefore very important

- In outcrop studies it is vital that the obtained sample is clean and free from any contamination, especially from weathered material

- In studies based on well ditch-cuttings the exact nature of the lithology may be less easy to determine*

- Samples apparently barren of microfossils are not necessarily always regarded as “non marine” – they may just be unsuitable lithologies for fossil preservation (e.g. evaporites, igneous rocks, metamorphic rocks, very coarse sandstones/conglomerates etc.)

As a general guide – the finer the grain size, the more microfossils can expect to be recovered.

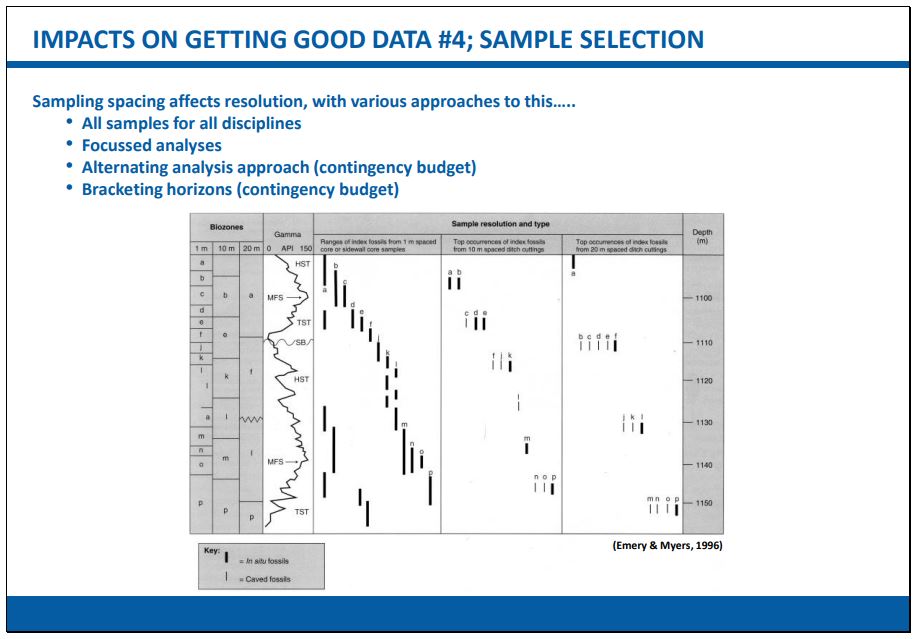

Sample spacing also has an influence on, for example, the degree of biostratigraphic resolution that can be achieved. As particle-physicists will tell you - “One can only resolve objects down to the wavelength of the light that is shone upon them.”

The most common forms of sample processing techniques are:

- Disaggregation – commonly used for calcareous, siliceous and phosphatic microfossils (e.g. forams, ostracods, conodonts, some diatoms and radiolaria) from un- or semi-consolidated sediments using one or more sieves. The bulk of the lithological matrix is washed away, or separated, leaving a residue in which the microfossils are concentrated. A moderate amount of chemical digestion (e.g. the use of hydrogen peroxide or weak acetic acid) may also be applied.

- Thin-section – used for various microfossils in hard limestones. Specimens are visible only in two dimensions but identification is possible if the section crosses the central part of the fossil. Such techniques require a specialist approach.

- “Smearing” – a quick method for preparing nannofossils which literally smears a thin lithological dust residue onto a slide. Some of the smaller diatom species may also be visible this way

- Suspension – a slower but more precise method for preparing nannofossils involving a suspension of lithic dust in water and allowing it to settle (or be centrifuged) before placing on a slide. Some of the smaller diatom species may also be visible this way

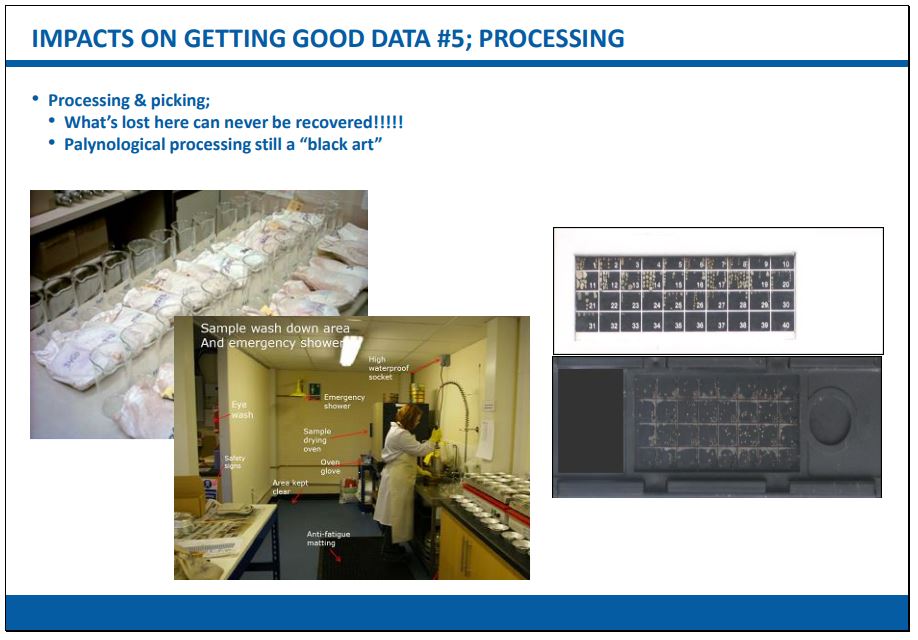

- Chemical extraction – a means of extracting organic-walled microfossils (palynomorphs) essentially by dissolving away siliceous rock from un-, semi- and fully-consolidated sediments and then oxidising the residues to make the palynomorphs visible. Several different toxic and corrosive chemicals are used which requires a specialist laboratory to perform.

*There are certain combinations of drill bit, mud type and whether or not the rotational speed of a drill string is enhanced by the use of downhole mud motors and turbines which have such destructive mechanical and thermal effects on rocks that effective microfossil recovery can be reduced to nothing. This can lead to gross misinterpretations of both biostratigraphy and paleoenvironments.